Source: Barrie Wilkinson

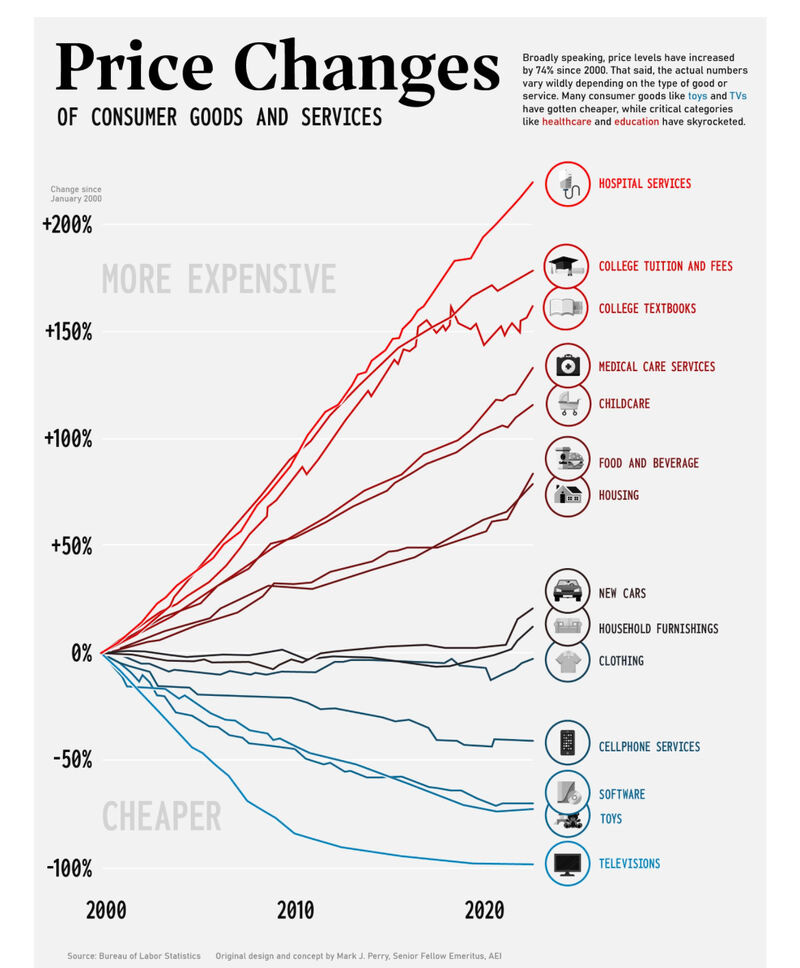

Recently, both Marc Andreesen and Azeem Azhar shared an interesting graphic (above) showing the evolution of cost in select industries over the past 20 years. Andreesen draws out the difference as being about regulation, that the regulated industries (healthcare, education, etc.) are those where costs have skyrocketed, while in the unregulated industries (manufacturing, etc.), costs have dropped significantly.

The same distinction can also be drawn in other ways. One distinction I have been thinking about for some time is products versus services. It is noticeable how little value things that can be mass-produced still hold, while anything that involves human labor has risen tremendously in cost. The distinction could therefore be drawn on the basis of products and services, since the prime examples at the very bottom and at the very top are TVs and healthcare. This may no be completely correct, however. Especially since some items have elements of both. Housing, for example, is clearly a product where the cost has not been reduced to near-zero, rather the opposite. Clearly 3D-printed houses could be made in large amounts, but real estate also has elements of a service in its signaling value.

Another useful distinction to draw might be between items where technology delivers economies of scale versus items where limitations (such as human time) prevent returns to scale. Andreesen uses the distinction to make the point that AI will not change everything, and not lead to full human unemployment. As he calls it, in some industries, AI is illegal. Eventually, things will change in those industries also, but it is a good reminder that in the near-term, the changes we will see due to AI are likely mostly in the space of scalable products. The cost of most products and services, both digital and physical, will fall to near-zero, especially when AI gets coupled with nanotechnology and atomic manufacturing, while cost disease will continue to plague products and services where human labor (especially one with regulated wages) is the biggest cost factor.

This means we will live in a world of abundance when it comes to things, but still not a full utopia where there is abundance of everything. Many people will still struggle to pay for healthcare, etc. Scott Galloway expressed it as “Grandma having the shiny rectangle (the iPhone), but having to eat dogfood”.

This has great relevance also for AI risk, since this reminds us that we will, at least to begin with, not have one monolithic type of AI risk. As typically described, the risk of AI is the risk of misaligned AGI. This is often a singleton that reaches human intelligence and then undergoes an intelligence explosion, with the risk that whatever goals the singleton has been provided with would prove to be incompatible with human survival in some way or other.

But it seems more likely that the scenario will be one where we have a wide variety of intelligences. Some of these at human level for some tasks, and some at human level for other tasks. It might not make sense to speak of an AGI that has overall HLMI (Human-Level Machine Intelligence). Rather what we’ll have is an intelligence state space with all kinds of types of intelligences.

Within this intelligence state space, it is likely that we’ll see Schelling points where more of these intelligences will cluster around the most useful use cases. For example, AIs useful in business or for military use. Eventually, we may well get to an instance of the classic AGI singleton superintelligence, but long before then, the main source of risk will be the risks associated with these varying intelligence state space Schelling points.

What makes these risks so difficult is because they will manifest on the other side of a singularity of sorts. Throughout recorded history, human behavior has remained fairly constant. Due to the stability of human preferences, human behavior is sufficiently predictable. This set of consistent human preferences, such as self-preservation, status quo bias, etc. are what allows us some kind of ability to peer into the future and forecast events.

But at some point, there will be more of artificial intelligences than there will be human intelligences. At least in areas of decision-making that really matter for the course of history. There may be specific types of intelligences that are very useful in specific domains. They may be PASTA that conducts research for new medicines, for example, Boardbots in boardrooms of businesses or military strategy AIs. As we’re seeing already now, Generative AI may have his own vector in intelligence state space, which will lead to risks around the loss of truth, for example, but perhaps these AIs will not become able to perform tasks that require contextually aware-decision making, and we will need other AIs, potentially non-LLM-based, for that.

That will be the real singularity. At a time when most intelligences are non-human, the forecastable patterns break down and that may prove to be the end of forecasting, at least of the kind we know now.